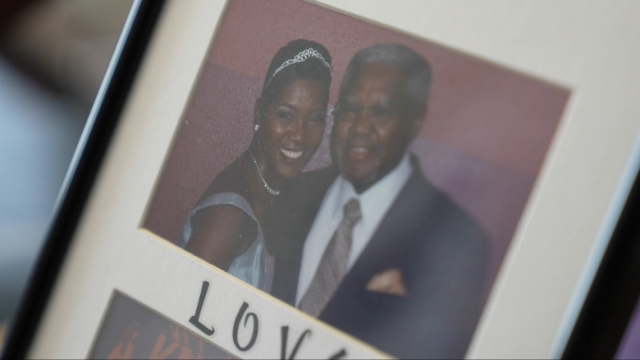

It's in the pictures Sylvia Waller lays out on a table that she remembers the best times with her dad, James.

Waller's father was diagnosed with Alzheimer's and passed away in 2017. In his final years, Waller took care of her dad, who lived alone.

"It was a tough one because the roles had changed. I was no longer his baby girl; I was his caregiver," Waller says.

There was no approved Alzheimer's treatment for Waller's dad, but she says the FDA approval of Leqembi offers hope.

Broader Medicare coverage is now available for Biogen and Eisai's Leqembi (the brand name for lecanemab) following the Food and Drug Administration's move to grant traditional approval to the drug that treats individuals with Alzheimer's disease. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services had previously announced this would be the case.

The treatment is a twice-a-month IV infusion for patients who are in the early stages of the disease. It has been proven to slow Alzheimer's progression by as much as 27%. Waller does worry about access to the treatment, especially for those in the Black community, who are twice as likely to develop Alzheimer's compared to those who are White.

SEE MORE: Alzheimer's disease is more prevalent in these parts of the US

Experts say health issues like higher rates of heart disease may play a role, but research has yet to officially identify a cause.

A big concern is the price. Medicare will cover most of Leqembi's cost of more than $26,000 a year, but many patients will be on the hook for roughly $5,300.

Add that to the total out-of-pocket costs of caring for an Alzheimer's patient, which The Alzheimer's Association estimates to be more than $238,000 on average.

"The majority of the people who have Alzheimer's are on Medicare, and they're not the 10% percent or the 1% who have money and a great retirement fund," Waller says.

Fabian Consbruck is a clinical psychologist outside Denver who works closely with the Hispanic community. Part of his work is giving patients tests to help determine if they have dementia.

"A lot of tests are not available in Spanish," Consbruck says. "A lot of my cognitive tests, I have to pull from Mexico, from Spain."

The Hispanic community is at risk of developing Alzheimer's or another form of dementia 1.5 times the rate of the White community.

SEE MORE: Why is there no cure for Alzheimer's yet?

Consbruck says getting help can also be hard because of the several steps and medical professionals dementia patients often need to meet with to get treatment. He worries Leqembi and other new dementia drugs being developed will be out of reach for many of his patients.

"Not only do they need to get a diagnosis, they need to get a referral back to the specialist, to their primary care doctor," Consbruck says. "The provider has to be caught up on the medication and feel comfortable with that medication."

Leqembi is meant to treat those who are in the early stages of Alzheimer's, which Jim Herlihy with the Alzheimer's Association of Colorado says makes access even more important.

"Every day 2,000 people advanced to another stage of the disease, so having access to these medications right now is critical for these people and their families," Herlihy says.

In 2022, with Alzheimer's awareness as her platform, Waller won Mrs. Colorado.

"At the time I was like 60," Waller says. "I've learned that no matter how old you are, you continue to grow."

Waller says while new drug developments are a major step forward, making sure people know the signs and symptoms are an important part of the fight against a disease that still has no cure.

Trending stories at Scrippsnews.com